In this image, gold leaf is overlaid with pigments of red, green and white. The red is that of the Christ’s blood which flows from his wounds. The green is that of the crown of thorns. The white is that of the Holy Spirit and the throne on which the Father sits flanked by angels. Although, this image is slightly taller than it is wide (118X114.9 cm), it looks like a square. If you were to draw two diagonal lines across the painting from the corners, they would intersect at Christ’s upper lefthand torso just above his heart. The asymmetrical distribution of colour is complemented by the symmetry of the composition. The more you look at this painting the more you see.

Of course, you are not really seeing the Trinity. As Jesus says in the Gospel of John: “Not that anyone has seen the Father except him who is from God” (Jn 6:46). This kind of representation of the Trinity, where the Father is shown as the ancient of days seated on a throne and holding the Son shown as Christ Crucified, and the Holy Spirit as a dove, was well established in Western Art long before 1400. In the nineteenth century German art historians named such images with the Father seated and holding the dead or dying Christ as “Gnadenstuhl” which means “seat of mercy”. However the term predates them as well. The mercy seat was the cover or lid of the ark of the covenant which was kept in the inner sanctuary of the Jerusalem Temple known to us as the Holy of Holies. Exodus 25:10 – 22 gives instructions about the construction of the ark. The wooden ark was to be covered in gold and its lid was to be made of pure gold. On either end of the lid there were to be two golden cherubim and the lid itself was called the mercy seat (Ex 25:17). And of the mercy seat the Lord says, “There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are upon the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you of all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel” (Ex 25:22). The length of the mercy seat is to be two and a half cubits. The cubit is an ancient measured based on the length from the elbow to the palm or extended middle finger. The English word comes from the Latin cubitum meaning elbow and the associated verb cubo meaning to lie down or recline. As a unit of measure the cubit was common to many cultures. It thought that in the Jewish usage a cubit was around 46cm, which makes two and a half cubits: 115cm which is the width of this painting. The more carefully you look the more you see!

The Day of Atonement the priest entered the Holy of Holies, and having offered incense before the mercy seat, he sprinkled it with the the blood of a bull as an act of atonement for his sins and that of the whole people (Lev 16: 27). This annual Temple ritual is picked up by the author of the Letter to the Hebrews. Christ is both priest and sacrifice. In our liturgy the second reading on Good Friday is always Hebrews 4:14-16. 5:7-9. The first reading for Tenebrae -that is from the Office of Readings- is Hebrews 9: 11-28. Each year we hear “he entered once and for all into the Holy place, taking not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption” (Heb 9:12). In this image then, gold represents the Holy Place of Hebrews, and Christ’s blood shed on the cross colours the robes of the Father and is reflected in the two cherubim. Their garments seem to me to flow. But this red is mingled with another flow of colour, that is the green. I said above that the green is that of the crown of thorns. However, it may be the other way around, for green is surely the colour of hope, and life, of youth and bliss. After all, this crown of thorns is unusually green. Personally, I associate it with the Passion narrative in Luke which has Jesus’ singular use of the word green. In Luke’s gospel when Jesus is led away to be crucified he encounters the women of Jerusalem and to them he says, “Do not weep for me, weep for yourselves and for your children …for if they do this when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?” (Lk 23:28. 31). Of course, his words refer to Jerusalem and its future fall. But an artist who had to be a specialist in pigment would make the same association.

Of course, any attempt to depict the Trinity must be highly symbolic. The whole history of such images of the God the Father is riddled with religious controversy, not least around the prohibition of images of God in the Decalogue. However, Christians have depicted the Trinity from early days.

The so called “Dogmatic Sarcophagus” in the Vatican Museum, which dates from 320 to 350 , shows the creation of Adam and Eve with God as three distinct but identical men, but beside this scene is another in which God talks to Adam and Eve in the garden and he is shown as just one man. It reflects the dogmas defined at Nicea.

Triple-faced heads, which to my eye are more than a little monstrous in appearance ,were once quite a common way to show the Trinity. One such head survived the Reformation carved on a misericord at Cartmel Priory, Cumbria in the mid 15th Century.

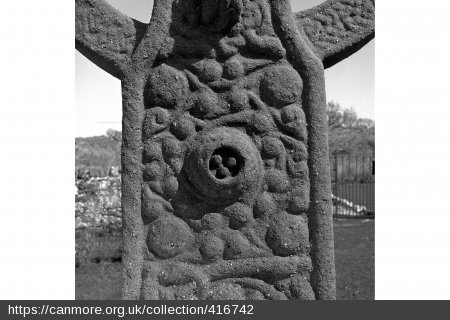

Also there are many early images which use abstract forms such as three equal circles inside a circle. On the high cross at Kildalton on Islay, which dates from the 8th Century, the Trinity is represented by three eggs in a nest!

There are a great many paintings which show the Trinity using the basic format of the mercy seat. Sometimes, Christ is no longer on the cross but is held pietà-style by the Father. We have one here in Edinburgh in the National Gallery , which came from the Collegiate Chapel of the Holy Trinity. The chapel once stood where Waverley Station is today. What survives are the wings of a triptych by Hugo van der Goes (active 1467 -82), one of which shows the Trinity.

For me what is most moving about the altarpiece in London’s National Gallery is the Father’s hands. The Father is much larger than the figure of the crucified Christ but it is the hands which draw me. They are strong and take the weight of the cross easily but the it seems to me that the upturned fingers touch the cross gently. Moreover, his arms are holding the cross out towards the viewer. For me then, this is the Almighty holding, not just the crucified Christ, but each of us in all our littleness. It reminds me of a favourite poem : “ Autumn” by the German poet Rilke.

Autumn

The leaves are falling, falling as from far,

as though above, were withering farthest gardens;

they fall with a denying attitude.

And night by night, down into solitude,

the heavy earth, falls far from every star.

We are all falling. This hands falling too –

all have this falling-sickness none withstands.

And yet there’s One whose gently-holding hands

this universal falling can’t fall through.

The Catholic Chaplaincy serves the students and staff of the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier University and Queen Margaret University.

The Catholic Chaplaincy is also a parish of the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh (the Parish of St Albert the Great) and all Catholic students and staff are automatically members of this parish.