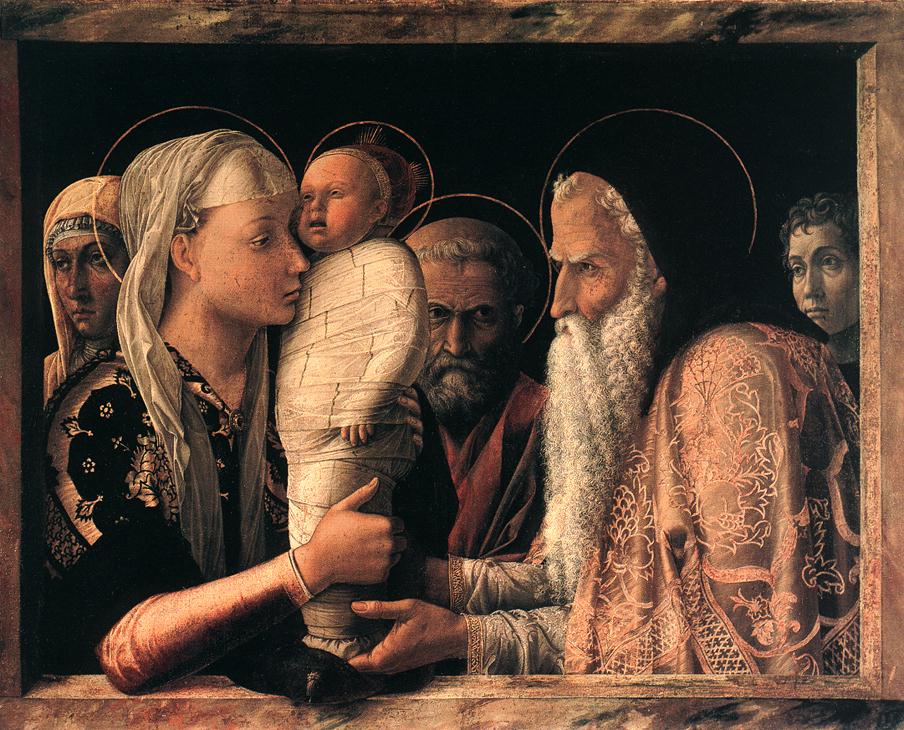

“The Presentation of Christ in the Temple”, Andrea Mantegna, c.1454, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche, Museen su Berlin.

This painting dates from around the time of Mantegna’s marriage to a member of the family of Giovanni Bellini. The two figures, left and right, are thought to be Mantegna and his bride. It has also been shown that 20 years later, Giovanni Bellini made another version of this painting. Bellini traced the central figures. Mantegna never made copies of his paintings. By contrast, Bellini’s workshop regularly produced copies. Bellini’s version of the Presentation became a “best seller” and his workshop produced many versions of this work and, using a similar composition, of the Circumcision of Christ. Therefore it would seem that for Mantegna this scene was a one-off work connected to his family life. In fact, with this presentation the young Mantegna broke new ground among artists in the Veneto and elsewhere in Italy. In Venice and Padua, icons of Our Lady and the child Jesus were used in public churches. In such images Mary and Jesus were often shown half-length and close up. But scenes depicting a story from the gospel always showed the figures full length. Here Mantegna combines the two types of image. This is a narrative scene. It captures that moment before Mary hands over the child to Simeon. Mantegna skilfully creates the illusion that the mother and child have entered into the very room where the painting hangs. Her right elbow is leaning on the illusionistic frame and the cushion on which the child is stood protrudes over the edge of the same frame. This fictional frame has been described as both lens and stage. It is as if we are given a window unto the sacred event, whilst the same event breaks into our world, offering us meaning and insight into ourselves. At the time, a new devotional movement, which became known as Devotio Moderna, had arrived south of the Alps and tracts such as “The Imitation of Christ” by Thomas A Kempis (1418-27) were widely read. This movement had a great influence among the devout, whether literate or illiterate. This movement emphasised a more personal connection with Christ and with his mother. Moreover, this Presentation strongly suggests the Passion to which Simeon alludes in the gospel. The child cries out as will Christ on the cross. His swaddling bands suggest the shroud. Indeed even the fictional frame is reminiscent of funerary reliefs from antiquity, which were certainly well known by Mantegna and his contemporaries. The only figure in the painting to be shown in full length is Christ, who is held upright by his mother almost in the same way that a priest elevates the host during Mass. It was common practice for the wealthy to have within their house a private chapel or oratory and you can imagine this painting hanging in such a space, darkened by shutters, so that the figure of Christ in his swaddling bands, Mary’s headdress and Simeon’s fantastic beard all glow in the half light. This painting must have had some direct link to the lives of Mantegna and his wife. Infant mortality rates were high and childbearing was a risky business. It would not be unusual, to say the least, for an expectant mother to seek the intercession and protection of the Virgin mother in those perilous months leading to a birth, or afterwards, to give thanks for a healthy child. To my mind, there is a link to what I see happening today in the lives of parents as they present their child for baptism, keenly aware that for now the child is dependent on them, but that with baptism a new path opens up before the child, and that one day, he or she will make his or her own way in the world, leaving both mother and father behind.

The Catholic Chaplaincy serves the students and staff of the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier University and Queen Margaret University.

The Catholic Chaplaincy is also a parish of the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh (the Parish of St Albert the Great) and all Catholic students and staff are automatically members of this parish.