How can you paint the Ascension? Artists have struggled. Sometimes you see just his Christ’s feet with the disciples below, as in Dürer’s “Little Passion”.

Another example is the scene at the top of “The Cloisters Cross” c.1100 and believed to have been made in Britain. It is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Sometimes, Christ soars up almost like a great bird. Giovanni Bellini painter Christ’s resurrection showing him in mid-air above the tomb, an image seems to have conflated the Resurrection and the Ascension. Put Moses and Elijah on either side and you have the Transfiguration. Many artists followed this composition with Christ floating above the ground so that it became hard to distinguish one subject from another.

Sometimes Christ is borne on powerful angelic wings as in Tintoretto’s “Ascension” at the Scuola San Rocco.

And how do you show the difference between the heavenly and the earthly realms? In Tintoretto’s work, heaven is light-filled and quite substantial. By comparison, the earth below is much fainter and insubstantial. Of course, the mystery of Christ ascending into heaven, and heaven itself, transcend our experience.

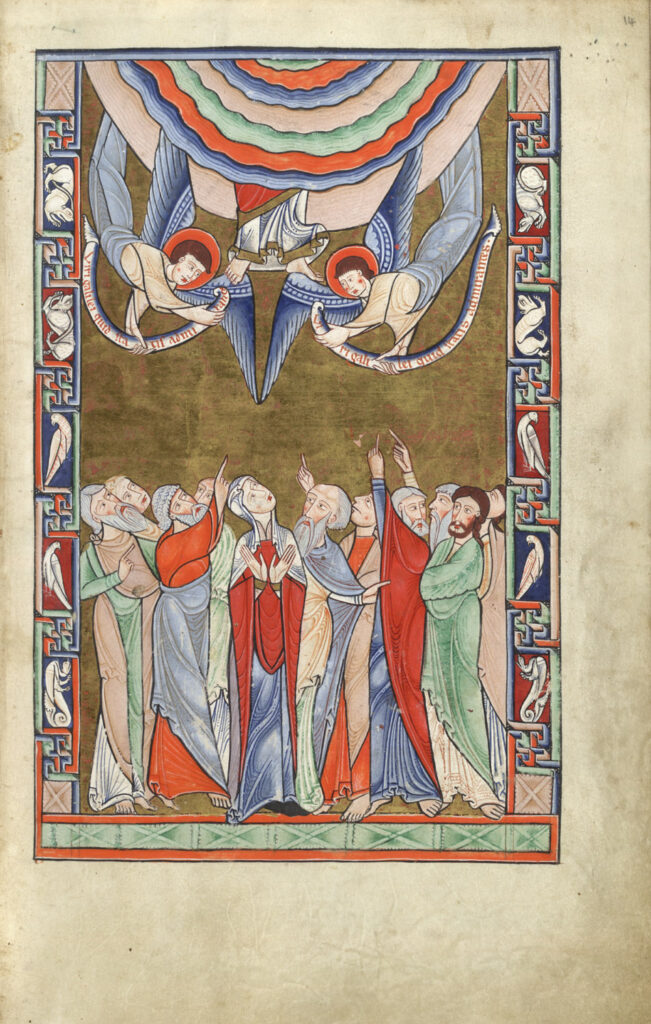

“The Ascension” from the Twelfth Century English Psalter shows heaven as a series of brightly coloured concentric circles into which Christ enters. The problem is more acute when you are painting in a Calvinist milieu, where there is a prohibition on depicting the divine, and a very pessimistic view of this life. However, in my view Rembrandt’s painting of 1636 is one of more successful images.

Christ ascends standing on a small cloud which seems to be continuous with the helm of his extensive cloak. Little cherubs look as if they are attaching themselves to the cloud as children might do were this a passing cart. But some of them look as if they are propelling it upwards. Their playfulness communicates joy. Christ is fully clothed in abundant white and radiates light. Yet we see that his feet are solidly planted on the cloud. We also see the wounds in his hands, once outstretched on the cross but now stretched out in glory, inviting those below to follow him. Were this a Catholic commission, the clouds above him might have opened to reveal the Father, Our Lady and the Saints. Indeed there is evidence that initially Rembrandt did paint the Father and the Holy Spirit but then thought better of it. Instead, we see the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove but also radiating light which falls on those below. The palm tree on the left, almost hidden in shadow, is a very Catholic symbol of the resurrection. On the right , the disciples are caught up into the scene above them. Some have hands joined but the one in the centre spreads his arms as Christ does, surely aspiring to follow him. This Christ is as human as they are, but his humanity is now exalted and glorified. This painting is one of a series of five paintings depicting the Passion of Christ commissioned for the Dutch Court through the offices of Constantin Huygens, secretary to the Prince of Orange. The original commission specified just two, which showed the elevation of the cross and the descent from the cross, which was to be after Rubens’ great work.

In the descent, Christ is shown in death. Christ’s broken body has none of the perfection of Apollo and the like. His agony now ended, it remains frozen on his features. The figure on the ladder to the left is Rembrandt himself, his face hidden in shadow. Rembrandt shows our human condition in all its frailty. Christ’s agony is raw and real. Within both these paintings light shines in a surrounding darkness, which effectively distances us from the scene, but at the same time draws us into contemplation. It is a bit like theatre and yet these figures are real flesh and blood. The call is to faith alone, for a Calvinist world is a radically fallen one and only Christ can lift us up. Christ, show clearly as one of us, both descends and ascends, his arms outstretched in love. One gets the impression that Rembrandt was no Calvinist!

The Catholic Chaplaincy serves the students and staff of the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier University and Queen Margaret University.

The Catholic Chaplaincy is also a parish of the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh (the Parish of St Albert the Great) and all Catholic students and staff are automatically members of this parish.